I was fifty-four in 2003 when I entered the California prison system. I estimate that the mean age was about half my age. Other men about my age were there, a lot of them were doing time for aggravated drunk driving, domestic abuse, and drug manufacturing. There were many first-timers and a fair number of long-timers. Although we had no common bond other than age, there was an unspoken knowing that the place was infested with young men blind to the pernicious situation they were in and too focused on worthless values seeped in hatred and bigotry.

I was fifty-four in 2003 when I entered the California prison system. I estimate that the mean age was about half my age. Other men about my age were there, a lot of them were doing time for aggravated drunk driving, domestic abuse, and drug manufacturing. There were many first-timers and a fair number of long-timers. Although we had no common bond other than age, there was an unspoken knowing that the place was infested with young men blind to the pernicious situation they were in and too focused on worthless values seeped in hatred and bigotry.

We senior offenders had experienced much change in race relations over the decades of our lives. The young inmates lived in a world of tinderbox hatred and constant repressed deadly chaos fomented by racism and razor-sharp lines of the different belief systems they had been taught.

Watching with horror at the recent display of white nationalists’ chanting neo-Nazi slogans in Charlottesville, Virginia—and the melee and death and mayhem that followed—bounced me back to the prison yard. The self-styled militias in camouflage gear screaming from my television reminded me of the difference my prison experience was with the more senior inmates than with the festering youth we shared that hostile environment with.

I found that the older inmates were easier to talk with about almost any topic. Older men can reflect on past life experiences that mold personalities with the passing of time. There was a familiarity based on shared experiences: military service, avoiding the draft, hurtful failed relationships, business failures, health issues, loss of success—full palettes of paint to verbally express the pains that come only with time.

I also noticed that we talked little about the hottest topics of all: racism, white nationalists, or hatred in general. These topics received sad-eyed, head-shaking looks of disappointment, often with an audible tsk tsk of condemnation.

In speaking with the older inmates, I saw that passage through time can fade race disparity and bigotry as men mature in confinement. I was encouraged to see that men could look beyond skin color, and other insane flashpoints of hatred, and try to do their time, as I did, without getting ensnared in the world of immaturity surrounding us.

My focus today is on the number of older adults living in the nation’s prison system. The numbers reflect serious issues that circle around how aging can be accelerated in prison, how medical conditions can be exacerbated in confinement, and that end-of-life care in prison is questionable. The latter issues are topics for another time.

What Do the Numbers Reflect?

The Bureau of Justice Statistics released a study on May 19, 2016, called “Aging of the State Prison Population, 1992–2013.” Here are highlights of that study:

- The number of prisoners age 55 or older sentenced to more than 1 year in state prison increased 400% between 1993 and 2013, from 26,300 (3% of the total state prison population) in 1993 to 131,500 (10% of the total population) in 2013.

- The imprisonment rate for prisoners age 55 or older sentenced to more than 1 year in state prison increased from 49 per 100,000 U.S. residents of the same age in 1993 to 154 per 100,000 in 2013.

- Between 1993 and 2013, more than 65% of prisoners age 55 or older were serving time in state prison for violent offenses, compared to a maximum of 58% for other age groups sentenced for violent offenses.

- At yearend 1993, 2003, and 2013, at least 27% of state prisoners age 55 or older were sentenced for sexual assault, including rape.

- More than four times as many prisoners age 55 or older were admitted to state prisons in 2013 (25,700) than in 1993 (6,300).

The statistics don’t account for race or economic status of older incarcerated adults. The study doesn’t reflect the meaning of older. In a New York Times Op-Ed dated August 18, 2013, entitled “Graying Prisoners,” Jamie Fellner describes specifics of older inmates with appropriate, poignant sensitivity about a serious situation. “Prison isn’t easy for anyone, but it is especially punishing for those afflicted by the burdens of old age.”

The numbers reflected by the Bureau of Justice Statistics are just that—numbers. The burgeoning number of older inmates requires special attention to what’s going on behind the faceless numbers. Humanitarian instincts dictate that early release of these individuals to appropriate care units, no matter the cost (build one less aircraft carrier), will act to alleviate the cruel and unusual treatment of so many aged incarcerated men and women for whom time is winding down.

I welcome your thoughts on the subject.

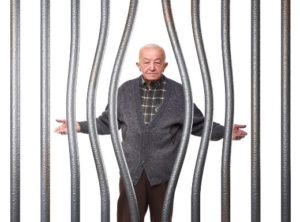

Image courtesy of shutterstock