Frederick Douglass wrote in his striking memoir, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass: An American Slave, that “The White children could tell their ages. I could not tell why I ought to be deprived of the same privilege.” Even asking your master about your birthday was, according to Douglass, “improper and impertinent,” and he added, “I do not remember to have ever met a slave who could tell of his birthday.”

Frederick Douglass wrote in his striking memoir, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass: An American Slave, that “The White children could tell their ages. I could not tell why I ought to be deprived of the same privilege.” Even asking your master about your birthday was, according to Douglass, “improper and impertinent,” and he added, “I do not remember to have ever met a slave who could tell of his birthday.”

Most reports have Douglass’s being born in February 1818 in Tuckahoe, Maryland. Douglass’s story reveals an extraordinary human metamorphosis from the horrors of being a slave to being revered for his oratorical and literary brilliance.

Prison Reform from a Different Vantage Point

The prisons in our state and federal systems have incarcerated three general categories of detainees: convicted criminals, political prisoners, and slaves. Where we fall in contemporary history determines the nature of incarceration to be endured.

Those convicted of criminal activity always know what crimes they’ve been found guilty of and how much time they will serve in prison. Political prisoners don’t always know what they’ve been charged with in terms of specific malfeasances against the state. Often, no specific sentence is known, and long and harsh confinements are dealt out by faceless authorities with some political agenda. In 1962, Nelson Mandela was sentenced to life in prison for conspiring to overthrow South Africa’s apartheid government. When the anti-apartheid movement gained a strong foothold in South Africa under the leadership of F.W. de Klerk, Mandela was released in February 1990 after twenty-seven years of confinement.

Slaves in America were political prisoners relegated as inhuman chattel and owned like some livestock commodity to be sold or bartered in an open and “free” market. African Americans were born into a system engineered to immediately strip them of their human birthrights by, as Douglass put it, “a heavy and cruel hand [that] has been laid upon us. . . . The great mass of American citizens estimates us as being a characterless and purposeless people; and hence we hold up our heads, if at all, against the withering influence of a nation’s scorn and contempt.”[1]

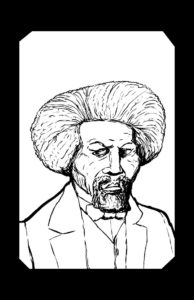

Picturing Frederick Douglass

Besides being an ex-slave turned leading abolitionist, an eloquent orator on human rights, and a seminal writer, Frederick Douglass was also a leading pioneer in photography. He visualized the power of frozen images. In their book, Picturing Frederick Douglass: An Illustrated Biography of the Nineteenth Century’s Most Photographed American, John Stauffer, Zoe Trodd, and Celeste-Marie Bernier beautifully display 160 photographs of Douglass with historical references to the art form and details about the times and events surrounding Douglass when each photo was taken.

The motivation behind Douglass’s interest in being the most photographed person of his century turns out to be unique, brilliant, and prescient. The authors noted above connect the historical dots for us:

Douglass quickly recognized this close connection between photography and freedom. He defined himself as a free man and citizen as much through his portraits as his words. The democratic art of photography echoed the freedom articulated in the nation’s founding document. His own freedom had coincided with the birth of photography, and he became one of its greatest boosters.

The authors discuss other reasons Douglass, a man who devoted his life to ending slavery and racism and to championing civil rights, was so enamored by photography:

- Born into slavery in February 1818, Douglass escaped from slavery in 1838, a year before Louis Daguerre and Henry Fox Talbot created the first forms of photography.

- He sat for his first known photograph (a daguerreotype) around 1841.

- He quickly recognized the close connection between photography and freedom.

- “He believed in its [photography’s] truth, value, or objectivity.” Most importantly, photographs “accurately captured a moment in time and space,” and “the truthful images represented abolitionists’ greatest weapon, for it gave the lie to slavery as a benevolent institution and exposed it as a dehumanizing horror.” Photos added an extra dimension to slave narratives, a genre mastered by Frederick Douglass.

- “Douglass recognized . . . that the power of photography depended on its circulation in the public sphere.”

Ultimately, Douglass’s recognition of the power of photography helped catapult him to becoming the most famous black man in the Western world, and thus he earned and acquired cultural and political power. His likeness came to embody his cause for racial equality.

Happy birthday to this man of many faces. His visual and oral gifts left behind a legacy upon which the world can ponder and learn volumes.

I always appreciate your comments and observations.

Image courtesy of 123rf

[1] Frederick Douglass, in a statement on behalf of delegates to the National Colored Convention held in Rochester, New York, in July 1853, as quoted in Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow.