Poetry is a penetrating art form that can give voice to the plight of incarcerated people. In his book Wounded Researcher: Research with Soul in Mind, Robert Romanyshyn studies the art of keeping the soul in mind when authoring psychological research reports. I was struck by the unusual juxtaposition of his research. One aspect of his four-part study applies, in my view, particularly to incarcerated people: how engaging in transference dialogues helps differentiate a researcher’s complexes about the work from the soul of the work.

Poetry is a penetrating art form that can give voice to the plight of incarcerated people. In his book Wounded Researcher: Research with Soul in Mind, Robert Romanyshyn studies the art of keeping the soul in mind when authoring psychological research reports. I was struck by the unusual juxtaposition of his research. One aspect of his four-part study applies, in my view, particularly to incarcerated people: how engaging in transference dialogues helps differentiate a researcher’s complexes about the work from the soul of the work.

According to Psychology Today, “the classic use of the term transference comes from psychoanalysis and includes the redirection of feelings and desires and especially of those unconsciously retained from childhood toward a new object.”

For the purpose of this post, I consider the new object to be the reality of mass incarceration, the psychoanalyst to be the poet, and the feelings and desires as those associated with a person’s losing his or her freedom.

I agree with Romanyshyn that poetry is an art of the soul. Whether you’ve ever taken a poetry course or you simply enjoy reading poetry, the expression of the human awareness of self and others is a literary study of human interactions with life and death. A concrete connection between psychology and poetry brings a sensitivity in which both processes seek the humanistic truths of any given moment.

An example of psychology and poetry that stoke the incarceration experience and give rise to empathetic understanding of imprisonment is found in Oscar Wilde’s The Ballad of Reading Gaol (jail). Written in 1897 after his release from a two-year prison term at Reading Gaol for homosexual offenses, the poem describes many aspects of Wilde’s prison experiences. Wilde’s pointed pen brilliantly extracts sensitivities of prisoners that are understandable in the head and in the heart. By way of example, I offer the following excerpt:

The brackish water that we drink

Creeps with a loathsome slime,

And the bitter bread they weigh in scales

Is full of chalk and lime,

And Sleep will not lie down, but walks

Wild-eyed and cries to Time.

But though lean Hunger and green Thirst

Like asp with adder fight,

We have little care of prison fare,

For what chills and kills outright

Is that every stone one lifts by day

Becomes one’s heart by night.

Wilde’s words are those of a man who endured two years in prison. During my two years of incarceration, I also experienced thirst (“green Thirst”) satisfied only after receiving permission to drink and measured and limited food often fouled by unknown ingredients (“chalk and lime”). Likewise, I endured night after night of tortured sleep in darkened confines, and every inmate cries inside for the passage of “Time” to move swiftly and with limited impact. Yes, I have experienced all of this, and I have witnessed the hardening of young men’s hearts each passing day of benign and boring incarceration.

Wilde—as the psychoanalyst—brings deeper and accessible meaning to mass incarceration realities through his poetic mirror of experienced horrors. His words encourage understanding and empathy through strong poetic transference.

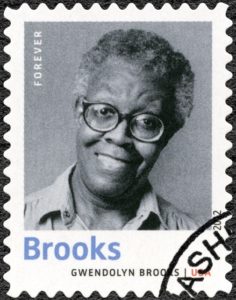

Meet Gwendolyn Brooks, Poet

Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000) was a prolific writer whose works include novels and poetry. In 1950, she was the first African American to receive a Pulitzer Prize for Poetry for her poem “Annie Allen.” By the time she was seventeen years old, Brooks was publishing poems frequently in the Chicago Defender, a newspaper serving Chicago’s African American population. Best known for her intense poetic portraits of urban African Americans, Brooks gives a vantage point for mass incarceration that is different than that of Oscar Wilde. Though not imprisoned herself, Brooks transcended the world of freedom into the castigated world of prisoners and tapped into humanistic and soulful themes that underscore her psychological views of the human condition in her art form.

According to the Poetry Foundation, “many of Brooks’s works display a political consciousness, especially those from the 1960s and later, with several of her poems reflecting the civil rights activism of that period.” While reading several of Brooks’s poems and reviews about her style and instincts, I came upon a short poem she wrote in 1981. The title is direct and the message illustrates her ability to identify the humanistic truths of incarcerated people:

I call for you cultivation of strength in the dark.

Dark gardening

in the vertigo cold.

In the hot paralysis.

Under the wolves and coyotes of particular silences.

Where it is dry.

Where it is dry.

I call for you

cultivation of victory Over

long blows that you want to give and blows you are going to get.

Over

what wants to crumble you down, to sicken

you. I call for you

cultivation of strength to heal and enhance

in the non-cheering dark,

in the many many mornings-after;

in the chalk and choke.

Gwendolyn Brooks

The themes Brooks focuses on are real concerns for the incarcerated. She uses darkness as a transference technique everyone recognizes and can relate to. As the poet-psychologist, Brooks dwells immediately on human experiences we all know: cold, heat, dryness, sickness, darkness, and disorientation. Remarkably, she uses poetic license to expand readers’ feelings of empathy, transporting her audience into an environment foreign to most, without apologizing for the trek. I read her imperative between the lines: Look at this. Take it all in. React!

Written eighty-four years apart, Oscar Wilde’s first-hand exposure to the world of forced incarceration and Gwendolyn Brooks’s outside perspective complement similar themes:

- Despair (over living conditions): food, drink, cold, hot paralysis, and incipient dryness that morphs into one’s own perpetuity.

- Deprivation: loathsome slimy water, chalk-filled bread, and the chalk and choke of each morning.

- Moral depravity: a wild-eyed relationship with the passage of time, asp and adder fighting, hardening of the heart, dark gardening back to moral fortitude, overwhelming dryness with mental sedation, and being crumbled down.

Conclusion

To me, the voice of poetry, coupled with the psychology of empathizing with the plight of others, is a key factor in moving prison reform forward. When people don’t care about any social reform movement, critical issues get sidelined and marginalization is perpetuated. The first step in getting real prison reform in this country is getting more people to care. Let the poets in all of us prevail through our transference dialogues.

Additional Resources

Read more about Gwendolyn Brooks and her writings.

View the video “‘My World’—Poem and Interview on School to Prison Pipeline,” by Mardia Cooper, who graduated with a BA in communications from Colby-Sawyer College. Her poem is about how underresourced communities provide limited opportunities within the education systems they encounter, becoming the point of origin for the prison pipeline.

Your comments and observations to continue the dialogue are always welcome.

Image courtesy of 123.rf